In memory of LALS alumn Rigo Padilla

Rigo Heading link

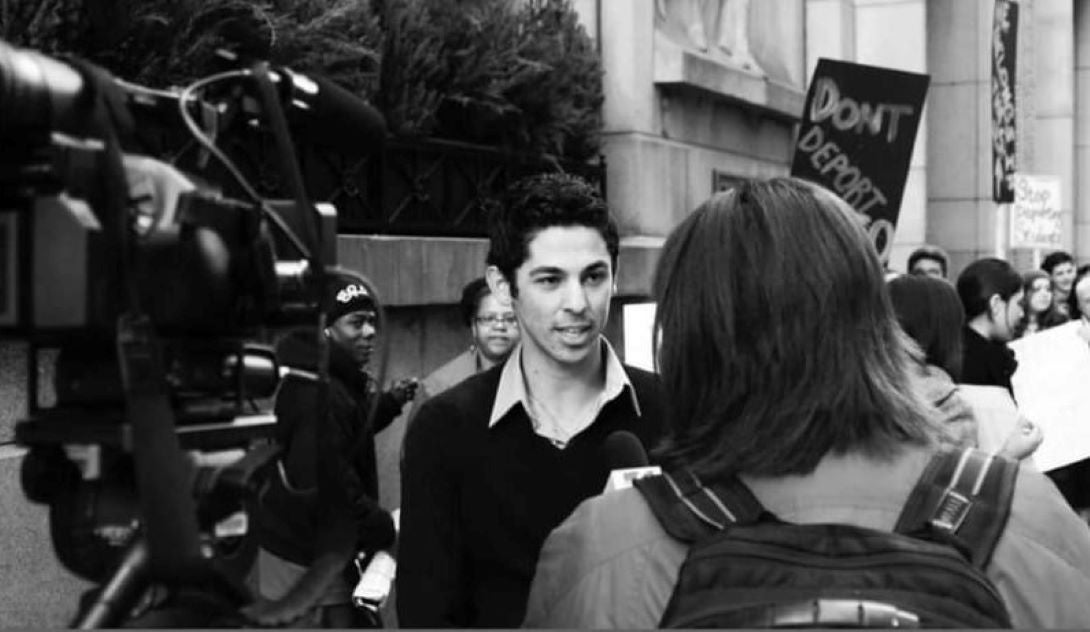

Rigo Padilla Pérez (1988-2023), College and Career Coach and Undocumented Student Support Specialist at Solorio Academy High School, has dedicated his life to ensuring that students of color obtain quality opportunities regardless of their background. Raised in West Town and Gage Park, Rigo’s lived experience revolved around the realities of gentrification, school closings, violence, and exploitation of immigrants in the city of Chicago. Since 2009, Rigo has been directly involved in the support of undocumented communities. He was a founding member of the Immigrant Youth Justice League (IYJL) and the Illinois Dream Fund. At the same time, he has been a leader in national campaigns to humanize undocumented people through advocacy and direct action.

In 2021 he was named a Surge Fellow by the Surge Institute, which recognizes young leaders of color, where he shared, “I feel that I am at a point in my life where I am the most capable to fully invest my time into continuing my professional development. At the same time, we are living in unprecedented times that have surfaced too many of the injustices that people of color face in this country. I am looking forward to connecting with others to not only analyze, but also continue creating positive change in our communities through multiple strategies – whether that be through education, continued dialogue, or direct action. My biggest hope is that I can gain experience and relationships to ultimately empower young people to continue making our communities healthier, safer, and more united.”

At Solorio High School, Rigo founded the Dream Team and Solorio Dream Scholarship where one of the most powerful annual events is the “Coming Out of the Shadows Day,” where undocumented students share their personal stories. Rigo was also a proud coach for the Solorio Academy Girls’ Soccer program.

Rigo holds both a Master of Arts and a bachelor’s degree in Latin American and Latino Studies (LALS) from the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC). There, he leveraged the importance of “going against the grain” [and along it] through critical discussions around race, power, and privilege, as a driver for connecting the past to the present, to dismantle systems of oppression.

Nena Heading link

On the Passing of a former Student, Activist and Friend: Rigo Padilla Peréz 1988-2023

I remember the day in 2009 when one of our students Rigo Padilla walked into my office wearing an ankle bracelet. He wanted to apologize and explain why he had missed class. “Profe, I was stopped this weekend for a traffic violation and then I was turned over to Homeland Security. “

My first reaction was that they were not supposed to do that. In one of my previous jobs as the Executive Director of a Commission on Latino Affairs, we had succeeded in getting Mayor Harold Washington to issue an order prohibiting the police department from turning people over to what was then Immigration and Naturalization Services. Every other Mayor since then had issued the same order. Rigo said, “I thought so too, but they did it anyway.”

He told me how he had come to the US with his parents when he was six years old, undocumented. I shared with him, that I had entered the US with “funny” papers when I was six and then paroled through administrative orders and finally “naturalized” thanks to the Cuban Adjustment Act. We needed to find similar solutions for him.

Thus began our journey to try to stop his deportation and as it turned out the millions of others who were being cruelly deported by the Obama administration. We initially reached out to friends in the administration. Disappointingly to no avail. A family friend and close advisor to the President, personally told me, “We simply cannot do anything. You just don’t know how many cases are out there. “

With the help of my husband, Matt Piers and other lawyers in his law firm, immigrant right organizations, activists , alumni and elected officials, we were able to prevail and finally succeeded in getting Rigo a temporary work permit. This was before DACA.

Yet Rigo’s case sparked a movement beyond his individual situation that had deep lasting impact on our university, scholarship, curriculum, activism, legislation and on my family.

I remember administrators becoming aware of how many undocumented students were part of our university community and this leading to important discussions about our responsibilities to them and changes in policies.

Our program became the epicenter of thinking and acting around immigrant rights. Community representatives gathered around a table in our conference room to discuss theories, history, and political strategies. In our classes we explored what it meant politically and personally to come out of the shadows. We thought of ways of comparing and contrasting displacement, across borders and neighborhoods. We added the right to stay to the popular right of movement scholarship. We debated notions of belonging, citizenship and even who could speak on behalf of the undocumented? Some argued that someone like Rigo who had recently been granted a work permit should lose their voice in the movement, while others defended him and advocated for building an expansive and inclusive community.

We discussed the sad irony of denouncing the first Black President of the United States for his draconian immigration policies, made all the more painful by the support and implementation of those cruel policies by a Latina, Cecilia Muñoz who in her prior work had won a MacArthur genius grant for her advocacy of immigration reform. We also came to the painful realization that the Dream Act was based on the terrible conceptual foundation that children could be saved but their parents had to be punished.

From these meetings and others, the first massive social movement claiming immigrants’ rights occurred in Chicago. Rigo was one of the main organizers. Faculty and students in our program delved into understanding why deportations at this moment in history, particularly the unprecedented numbers. How did social movements emerge? How could they be successful? An important book edited by Amalia Pallares and Nilda Flores-Gonzalez titled Marcha: Latino Chicago and the Immigrant Rights Movement explored these questions. Others followed. We applied and successfully obtained from the university an Immigration Cluster which allowed us to hire new faculty focusing on immigration. We added courses on multiple aspects of immigration. And even today immigration studies and scholarship continue to be a central tenet of our program.

We lobbied and organized for new university policies and eventually created a position for an advocate for undocumented students. We helped change state legislation to guarantee that undocumented state residents were charged in-state rates and not the exorbitant international rates. Our Senators and Congressional representatives worked diligently to try to pass. immigration reform. Rigo was involved in all these efforts and many others.

Rigo was also a friend and deeply touched our family. Our daughter Alejandra met him at a rally in support of the Dream Act. Rigo’s case compelled Paola our youngest to concentrate on immigration studies. She included an extensive review of Rigo’s case in her undergraduate thesis. He was also one of her inspirations to organize a protest of President Obama’s immigration policies when he came to speak at her 2012 college graduation. As they crossed the stage, many of Barnard graduates wore pins with Obama’s image and a message: “Yes You Can stop deportations!” They all became friends and part of a network of UIC scholar/activists.

Rigo was at the center of pro-immigrant struggles and eventually went on to work with other high school students who like himself were undocumented. He was thoughtful, reserved and perhaps a little shy, yet he was thrust into a limelight he never sought. I cannot help but think that what he carried on his own body, the pressures of the assumed leadership position he never wanted but felt obliged to accept and the precariousness of his own situation contributed to his deteriorating health. He willingly made a commitment to try to help others who were in his situation, even at the expense of his own professional growth and health. He was allowed far too little time with us, yet he touched us all in a very profound way.

Maria de los Angeles (Nena) Torres

Distinguished University Professor

University of Illinois Chicago/ Latin American and Latino Studies Department